Why I Couldn't Stay at Business School: Notes on Dropping Out

This is the first time I’ve really tried to write down why I dropped out of business school. It’s probably going to take a few entries to get it right, a series of attempts to figure out why I felt so out of place. Looking back, it wasn’t one big explosion. It was a slow accumulation of moments where I felt like I was wearing shoes on the wrong feet.

This is the first time I’ve really tried to write down why I dropped out of business school. It’s probably going to take a few entries to get it right, a series of attempts to figure out why I felt so out of place. Looking back, it wasn’t one big explosion. It was a slow accumulation of moments where I felt like I was wearing shoes on the wrong feet.

It was theater, not education.

That’s what I wrote in the margins of my notebook during my third week. Sixty of us were acting out a negotiation between a pilot’s union and a legacy airline. My partner was pounding the table, demanding a 4% hike in pension contributions. I was supposed to be the airline CEO, pleading poverty due to rising fuel costs. We were using a script written in 1998

I didn’t go to business school to become an actor. I am an engineer by trade. I spent five years optimizing and debugging code. I went to business school because I wanted to leap. I tried to stop fixing the machine and start steering it. I thought they would hand me the manual for the modern world.

Leaving was the only logical outcome

Looking back now, dropping out wasn't a failure; it was a course correction. It saved me two years of studying a map for a territory that no longer exists. I realized that if I stayed, I would graduate perfectly equipped to manage a company in 1990. But I wanted to understand why the rules of the game feel so broken today.

Have you ever sat in a meeting where everyone is furiously agreeing on something that you know, deep down, is fundamentally irrelevant? That was my life there.

Here is how business school teaches you the world works: We live in Capitalism. This means free markets. If you make a better toaster than your neighbor, you win. The market is the judge.

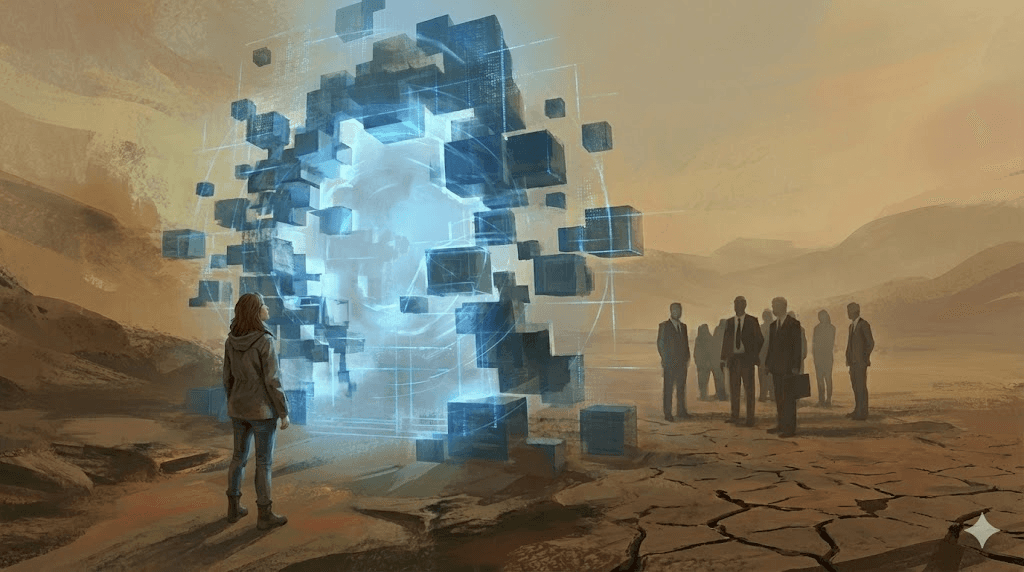

Inspired by Varoufakis's book "Technofeudalism," I would argue that Capitalism is dead. It’s been replaced by something closer to the Middle Ages.

Think of it this way: In the old days, you went to a town square to sell your goods. It was public. Today, we don't go to a market. We go to Amazon, the App Store, or Facebook. These aren't public squares; they are private estates owned by "Cloudalists", the new feudal lords.

If you sell on Amazon, you aren't competing in a free market. You are a serf working on Jeff Bezos’s land. You pay him "rent" to exist there. He controls the algorithm. He isn't competing with you; he owns the universe you live in.

Business school was teaching us to react to market signals, but the signals are now rigged by the platform owners. We were analyzing case studies of Ford and GE, while the real power had shifted to the cloud, where the rules of supply and demand are rewritten by the landlords of our digital lives.

I didn't quit because it was too hard. I quit because it was irrelevant

That was the disconnect. In that amphitheater, we were arguing about profit margins, assuming we had leverage. But in this new reality, profit isn't the main goal.

As an engineer, you don't argue with the data when it contradicts the model. You change the model. I couldn't learn to navigate this new feudalism by role-playing the old capitalism. We have bigger fish to fry than a union dispute from the nineties. And I need to find a kitchen that knows the fire has changed.

Get Athos Pro